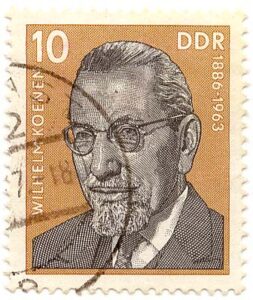

After an early period of militancy, Koenen became more of an org man than many people included here, but his remarkable and largely unknown history is illustrative of how far the German left’s roots lay in the revolutionary years and upheavals of 1918-1923 and how difficult the British state made it for even a Reichstag deputy who was a Communist to get into the UK.

After an early period of militancy, Koenen became more of an org man than many people included here, but his remarkable and largely unknown history is illustrative of how far the German left’s roots lay in the revolutionary years and upheavals of 1918-1923 and how difficult the British state made it for even a Reichstag deputy who was a Communist to get into the UK.

Born in Hamburg, the son of a socialist carpenter and a cook, he joined the SPD in 1903 and later became one of their newspaper correspondents. But in 1917, he joined the USPD and became the Commissar of the Worker and Soldiers’ Council for the Halle-Merseburg district in 1918/19. Here, in Central Germany, he and the Left Independents did a remarkable job of organising the railwaymen, the coalminers, and workers in the chemical industry and organising a provisional regional workers council.1 In 1919, he joined the KPD, and was elected to the National Assembly.

During the Kapp Putsch, he helped organise the strike which stopped the putsch. A delegate to the Trade Union confederacy, he argued that a workers government be formed but these proposals did not garner much support.He became the editor of ‘Berlin am Morgan’. Between 1920 and 1932, he was a KPD member of the Reichstag, a city councilor in Berlin from 1926 to 1932, from April 1932, a member of the Prussian state parliament and a member of the KPD’s Central Committee. He was one of some 40 people at the ill-prepared and ineffective secret ‘Sportshall’ meeting of the KPD Central Committee on 7 February 1933 to discuss the KPD’s reponse to the Nazis.

Koenen fled Germany in June 1933 on the decision of the KPD leadership (who had technically to give permission), first going to Saarland, then to France, then Czechoslovakia, where he was involved in dangerous border work with a group of left-wing ‘Red Mountaineers’ who worked with equivalent groups of German mountaineers in ‘Saxon Switzerland’ to get wanted people out of Germany. (For further information, see ‘ ‘Anti-Nazi Germans’.)

Koenen was repeatedly refused entry to the UK, despite being a Reichstag Deputy. He visited in December 1928, arriving in Harwich, but was warned to leave. The Home Office decided he should not be allowed to land again.Even then, Special Branch had a detailed trajectory about him eg that he was a Sparticist who had escaped from Hamburg Police on 23.5.1919, that he was part of Communist disturbance in Vienna, on 1.12.21 and a host of his more official functions, which suggests, at a minimum, a high level of cooperation between the German and British ‘intelligence services { National Archives, KV 2/2/98).

Somehow he got in again in December 1928 when he spoke at an election rally in Battersea on behalf on Saklatvala, a Communist MP who was also deeply involved in the League against Imperialism. Then, in May 1932, Koenen tried to land but was refused entry at Dover. This was in line with a Home Office circular (B.2764) from 1 January 1929. Somehow, they knew beforehand that he was arriving, according to a letter from Kell, Director of MI5 and a dedicated anti-Communist, which reafiirms the existence of an intelligence link with the German secret service. Koenen was interogated – it was,the report stated, all very friendly, before being put back onto the ship that he had just arrived in.

Koenen came back here to attend the mock trial, devised by Munzenberg, of the supposed Nazi instigators of the Reichstag fire, held before international judges in London. The Daily Herald of the 18.9.1933 reported that he was allowed to land owing to a mistake made by the immigration officer. The Home Office expressed great surprise. .

Then, though further details are not known, in December 1933 he left here for Copenhagen, returning in January 1934. A memo addressed to M15 states, crossly, that he somehow slipped back into the UK, probably, it states, using false papers.(They were obsessed by forged papers.) He must not be allowed back in again. (KV 2/27798).

Though MI5 records cannot be assumed to be reliable, Koenen may well have been a Comintern agent in Spain ( was he in Spain some of the time between 1936 and 1938?) and in 1936, a member of its Paris Secret section. While Koenen was living in Paris, Munzenberg, one assumes still acting on behalf of either the KPD or the Comintern, sent Koenen to the UK to pursue anti-fascist activities ( from document dated April 1936, PF40504). One remarkable document from Moscow in the same file also suggests that up till 1936, Moscow saw Koenen as their man. Dated March 1936, it chides him for not putting into effect the PolitBureau’s resolution for the union of ‘The Committee of Action for Liberty in Germany’. He needs to sign the document immediately. Though no other detail is given, this suggests that Koenen may not have been that keen on the new Popular Front line adopted by the Comintern in July 1935 (though not yet by by the KPD). In September 1937, Koenen does sign the ‘Appeal for a German Popular Front’ issued by members (note not the organisations of) the SPD, KPD etc, published in l’Humanite.

In February 1937, Ellen Wilkinson2, a Labour MP, came to Koenen’s aid and obtained a British permit for Koenen on the basis that D.N. Pritt3 guaranteed him ‘a living’, though it was on the understanding that he was on his way to Mexico or the USSR (Whoever it was in MI5 reasonably commented that this assurance was not worth the paper it was written on!) (Pritt, a barrister, was a member of the Labour Party with sympathies for the USSR at the time.) Wilkinson wrote in February 1937 that she felt a responsibility for him ever since his involvement in the Reichstag fire counter-trial. Koenen must have again left the UK as there is a further letter to Wilkinson that in December 1938, he was readmitted but only for two months. After that, he approached her again to ask for her help: the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslavakia and Ellen Wilkinson then both accepted full reposbibility’: his visa was extended till June 1939 and then till July 1939 (Home Office file K.15623) Straight after this note, it states: ‘This man is, from our point of virwe, most undesirable’. And in a separate document, it states:’ We asked to be allowed to see the files of the Czech Committee before the renemal of the permit… This request appears to have been overlooked’.

Most extraordinairy, in the same document originally from November 1938, the Home Office states: ‘Discussed matter with MI5, who advised against admission of these Communists. Every probability they would engage in anti-Nazi propaganda that would endanger our relations with Germany“. ( My italics)

It is not necessary to follow all the details to appreciate that the British state was doing everything it could to keep out Koenen. Yet Koenen was a committed and courageous anti-Nazi, much wanted by the Nazis.The constant threat of ending up back in Germany must have fuelled insecurity. Neither influenced MI5.

MI5 also -erroneously- believed Koenen was head of the Communist cell in the UK. (For a more accurate account, see the biographies on S. Moos and the Kuczinski clan!) They also suspected he was forming a London Bureau of the Comintern! MI5 continued to keep a close watch on him. There are a series of reports from May, 1939, stating that men of an alien appearance called on him. ” Judging by the appearnce of the tenants [of the house he lived in] “they belong to the Communist persuasion”! (Signed HHIB6) One indication of how seriously Koenen was being taken is that one missive was signed by Hollis, later director of MI5 (about whom many questions have been subsequently raised).

He was then taken into custody as an “enemy alien” in 1940 and sent on to Canada but brought back to the Isle of Man in December 1941. He was then released following the intervention of Eleanor Rathbone, MP, and D.N.Pritt. On February 26th, he appeared before the Home Office advisory committee whom he assured he would not take part in British politics. But he did not see this as debarring him from involvement in German exile politics.

He had become a founding member of the “Free Germany” movement in London where, however, his absence seems to have given rise to serious political wrangles with Kuczinski, amongst others, in part over the degree to which Germans, given the low level of resistance, were responsible for Nazism. This led on to his deposing Kuzcinski from the leadership. (Charges of who was spying for whom also abounded.)

In 1945, he returned to Germany and took part in rebuilding the KPD where he appears to have taken the Party line.

1Broue, The German Revolution 1919-1923, p 269

2Wilkinson, originally on the left of Labour, visited Nazi Germany in 1933 and wrote ‘Why Fascism?’, which condemned the Labour Party’s gradualism, arguing for grassroots workers’ unity against fascism . She was to become Minister for Education in the 1945 Labour Government by when she seems to have left her radical roots behind.

3In April 1933, Pritt amongst others signed a letter urging the Labour Party to form a United Front with the CP etc against fascism, rejected at that and the following year’s Party conferences. A lawyer, in 1934 he successfully defended the veteran socialist Tom Mann, on trial for sedition and won damages against the police for the organisers of the National Unemployed Workers Movement. From 1936, a, Labour MP and member of the Labour Party’s Executive Committee, he was sympathetic to Stalin, including over the Moscow Show Trials. In 1940 he was expelled from the Labour Party for defending the Soviet invasion of Finland. He later defended many of those accused in the anti-colonial struggle including those accused of being MauMau.