an extract from Anti-Nazi Germans

Martin Monath was a Berliner of Jewish heritage who had been a leading member of the German section of the socialist zionist organisation Hashomer Hatzair. This organisation encouraged Jews to emigrate to Palestine to build a Jewish nation state, but they wanted the new country to have a socialist economy. Monath’s brother and sister went to join a kibbutz in Palestine but, for reasons that are not entirely clear, he did not follow. While the Nazi regime destroyed the organisations of the workers’ movement, they tolerated the zionists until 1938, seeing them as organisations trying to help Jews leave Germany. Hashomer Hatzair’s Hebrew language magazine was permitted in Nazi Germany, even to the extent that it published some of Trotsky’s articles. Martin Monath was clearly influenced by these articles and, when he managed to flee to Belgium, he joined the Belgium Trotskyists, one of whose leaders was Abraham Leon, who had been one of the leading figures in the Belgian section of Hashomer Hatzair.

Monath was a delegate to the first European conference of the Fourth International in 1942 held near Paris. He stayed in Paris and began production of a small newspaper Arbeiter und Soldat (Worker and Soldier), with the aim of spreading revolutionary ideas and organisation amongst the German occupying forces.

The Trotskyists rejected the idea that World War II was a war between “democracy” and “fascism”. Trotsky and his co-thinkers based their policies on the idea of “Transform the imperialist war into a civil war against the imperialist bourgeoisie”. They rejected the idea that the struggle against fascism required the workers’ movement to subordinate itself to the “democratic” bourgeoisie.

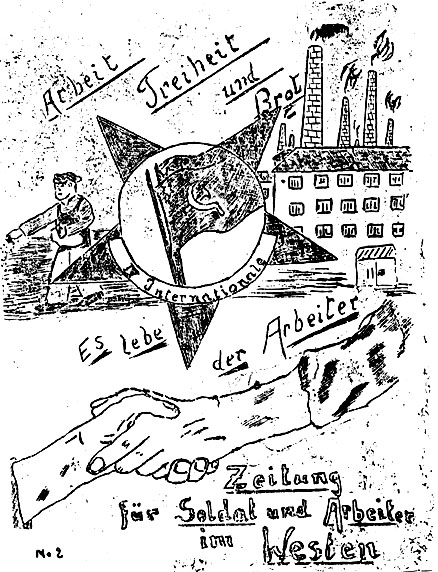

During the first half of 1943 in Brest, in northwest France, the Nazis were constructing a massive U-boat bunker. In February of that year, the Red Army had smashed the Wehrmacht at Stalingrad, in July, Mussolini had been overthrown. Many German soldiers started to realise that the war was not going to end well for Hitler. A German soldier in Brest met a young French postal worker, Robert Cruau, and they started to talk about the situation. The soldier was the son of a former communist official, so he understood something about socialism. Robert Cruau revealed that he was part of a clandestine revolutionary movement, while the soldier spoke of his small group of like-minded soldiers. Robert put this soldiers’ committee in touch with a printer and they started to produce their own small bulletin for other soldiers in Brest called Zeitung für Soldat und Arbeiter im Westen (Newspaper for the Soldier and Worker in the West). They continued to meet regularly to discuss politics, but there were language difficulties, so Martin Monath was invited to one of the secret meetings in the summer of 1943. He brought along copies of Arbeiter und Soldat. In particular, they discussed why the official communists were calling for an alliance with the bourgeoisie against Hitler.

However, the Gestapo was able to introduce a spy into the group, Konrad Leplow. Enthusiasm for the prospects led to a lack of security and the Gestapo were able to raid a meeting of 10 soldiers. During October 1943, 25 German soldiers and 25 French Trotskyists were arrested. Twelve soldiers were immediately executed, while others were deported to the Eastern Front or to concentration camps, but Martin Monath was able to escape.

By early 1944, he was back in Paris and resumed publication of Arbeiter und Soldat. However, his luck ran out in July 1944 when he was arrested by the French police who turned him over to the Gestapo. He was tortured and shot just days before the general strike and insurrection broke out in Paris. 1

The approach of Arbeiter und Soldat was very different to that of Soldat im Westen and would probably have appealed to a different audience amongst the German soldiers. Or maybe any anti-Hitler sentiments would be attractive to a soldier who was fed up with the war and who was looking for a way to actively oppose it. The Trotskyist organisation in France only had a fraction of the resources given over to Travail allemand, so it is unfair to make too many comparisons. 2

WHAT DOES ARBEITER UND SOLDAT STAND FOR?

Is proletarian revolution coming?

Once again the spectre of communist revolution haunts the globe. In Germany Göring invites his “compatriots” to eliminate any German worker who speaks out about the coming proletarian revolution. Goebbels writes that “this war is synonymous with social revolution”. He uses exorcisms like this and others to try and escape the abyss of the now inevitable revolution. In Britain even the Tories, hoping to calm the proletarian tide, are talking of projects to improve the well-being of the masses after the war. In the United States high finance warns “If Stalin goes over to the Trotskyist theory of world revolution”—or, more precisely, if communist revolution breaks out—“we will crush it with arms”. In the name of the capitalists of the United States and the rest of the world, Roosevelt demanded that Stalin dissolve the Comintern. In Russia—yes, in Russia!—the Stalinist clique has indeed dissolved the International. The Russian bureaucrats have called for revenge against the German people and they have made great pains to prove to their dear allies their honourable intention to crush any communist revolution in the egg.

This is how these gentlemen view the danger of communist revolution, and this is how they prepare to greet it. But what of the workers, the hundreds of millions of exploited? Most importantly, what of the German proletariat? Are we really on the threshold of communist revolution, or will the ruling class have more to show for itself than the bloodbath of peoples it has organised in its quest for profit?

The question must be posed even more sharply. These gentlemen would have no objection to an uprising against Hitler’s clique which ushered in victory for the Anglo-Saxon imperialists: on the contrary. It is with this goal in mind that working-class districts are bombed day and night with the aim of heightening exasperation and thus pushing the desperate masses into revolt. An uprising would have its place in these heroes’ programme, as long as it brought some dictator to power or, in the worst case scenario, some sort of “democratic” regime, which they would simply require to respond to the wishes of Anglo-American capital.

But revolutions are a dangerous thing, and a lot can change. If millions of workers took to action they may well go beyond that and fight for their own objectives, creating a Soviet Republic as the basis for socialist construction. But is there any sign that the leaders in Washington, London and Moscow will not get their way? Didn’t the German proletariat let the revolution slip through its fingers once already? Haven’t Himmler’s terror and Goebbels’ brutal propaganda broken the German working class and completely destroyed its faith in its own revolutionary strength? Can anyone really believe that the European revolution will go beyond the tight confines of the Anglo-Saxon imperialists’ plans? That is the question posed. 3

Robert Cruau

André Calvès writes:

“At the beginning of 1943, Comrade Robert Cruau, who had fled Nantes where he was wanted, actively began directing propaganda at German soldiers. The clandestine newspaper “Arbeiter und Soldat” as well as some mimeographed flyers were distributed in Brest.

In August 1943, Cruau set up a network of 27 anti-Nazi German soldiers. It consisted of a few former German communists but mainly young men. Robert Cruau said that the old remained opposed to Nazism, but they were defeated and very few could take the decision to engage in underground work. On the other hand, although German youth was to a large extent intoxicated by Hitler’s propaganda, it was nevertheless among the young people that we could find the most combative elements to form the German revolutionary movement.

A notable part of the clandestine articles explained to the German soldiers the real conditions experienced by French workers under the Nazis. The majority of German soldiers did not know much. The articles ended with calls such as: “Do not make yourself the guard dogs of capitalism and Nazism. Help young French workers fight against deportations”.

But we could only produce 150 copies, what a drop in the ocean! However this drop of water had enabled us to contact 27 German soldiers. As soon as these soldiers had taken this step, it was not possible to make them believe that a just peace would come from the colonialist British Empire, it was not possible to make them respond to the calls of a General Von Paulus speaking on Radio Moscow.

To find a common ground of understanding and struggle with the German proletariat, it was necessary to speak of “Workers” and not “Nationalism”. The clandestine leaflets also spoke of the causes of the war, and here too, the correct explanation, the Marxist explanation, could only be understood: Hitler makes war, but Ford, Schneider, Krupp, Churchill and company have made Hitler. Finally, the only solution was the struggle for the proletarian revolution in Germany as in France.

In October 1943, a traitor provoked the destruction of the Trotskyist organisation in Brest. The Nazis immediately killed Robert Cruau. Many other comrades were deported to Ravensbrück and Buchenwald, then to Dora”. 4

1 Flakin, Wladek , 2018, Arbeiter und Soldat. Martin Monath—Ein Berliner Jude unter Wehrmachtssoldaten, Stuttgart: Schmetterling Verlag

2 Craipeau, Yvan, 2013, Swimming against the Tide: Trotskyists in German-occupied France, London: Merlin.

3 Arbeiter Und Soldat, For Revolutionary Proletarian Unity, No. 1 July 1943 – translated by David Broder

4 Calvès, André, 1984, Sans bottes ni médailles: un trotskyste breton dans la guerre, Lyon: La Brèche.