Heinz Kamnitzer (1917-2001)

Heinz Kamnitzer (1917-2001)

Kamnitzer, born in Berlin, became a member of the Socialist School Association in 1931.1 Aged only 16, he was arrested in 1933 because of hisillegal political work. After release, he fled to England and continued his studies at a Polytechnic in London.In 1935/36, he left for Palestine where he became an apprentice carpenter but returned soon afterwards to London. In 1938, he became a member of the exiled KPD group. Still only in his early 20s, he wrote for and then became editor of the magazine: ‘Inside Nazi Germany’, the publication of the Free German League youth organisation. What happened then is not clear. It appears that the British Communist Party withdrew its financial backing from the magazine a few months after the signing of the Hitler-Stalin pact, and the paper folded in March 1940. At the same time, Kamnitzer was expelled, excluded or resigned (depending on which version one reads) from the Communist party in 1940 because of the interest Scotland Yard was showing in ‘Inside Germany’.2 He resumed his membership in 1945.In 1940, Kamnitzer was interned and then sent to Canada but returned to London in 1942. He became an editor for the ‘business’ newspaper: ‘Petroleum Press Services’, an organisation which, as far as I can see, was not, as it sounds, a capitalist enterprise but was researching into the importance and availability of oil supplies to the USSR and Germany!3 He also became a director of the Free German Cultural Association and an employee of the ‘Jewish Aid Committee for the USSR’, though again I was not able to establish what organisation this exactly was.

In 1946 Kamnitzer returned to Berlin from exile where he made a successful academic career for himself as a writer and historian and became a vocal supporter of the East German Government.

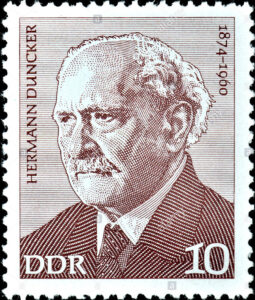

Hermann Duncker ( 1874-1960)

Hermann Duncker ( 1874-1960)

I am including a very brief biography of Hermann Duncker although his time in the UK was very short because his and his families’ story gives us an insight into how hard exile could be.

He married Kate Doll, a member of the KPD and a socialist women’s activist. Their first son, Karl, a famous psychologist, committed suicide in 1940 in exile in America. The youngest son, a Communist, was the victim of the purges in the USSR and died in a Soviet labour camp.

Originally a member of the SPD, Hermann Duncker was a co-founder of the Spartacus League, after taking part in the 1918 Revolution, and was one of the founders of the KPD. (Later, he came into conflict with the Comintern over his rejection of the Hitler- Stalin pact.)4

Arrested immediately after the Reichstag fire, he was released in November 1933 and then had to live under police supervision. He fled to Denmark in 1936, then to the UK and, for reasons i have not been able to establish, in 1938 to France. He then somehow moved country (and language) for a fourth time and got to the US where he joined his wife. In May 1947, Kate and Hermann Duncker went to E. Germany (despite the fate of their younger son). He joined the SED and was well regarded.

Hans Siebert (1910-1979)

Siebert first joined the USPD, then the SPD and then the KPD in December 1931. In his early 20’s, the local KPD put him to work building the communist youth movement and propagandising for the 1932 elections. He also became involved with the ‘Friends of the Soviet Union’. In his new post as a teacher in an elementary school, he participated in the organisation of school strikes (further details unknown) and was dismissed from his teaching post in February 1933 i.e. immediately after the Nazis had taken power but before the Reichstag fire. In April 1933, he was arrested for political reasons and not released till 1935.

In September 1936, he fled to the UK, where he seems to have continued teaching in some capacity and became the head of the German section of the Teachers Union (numbers unknown!). From 1937-1940, he was the secretary of the Committee for Spanish refugee children, a cross-party group, which helped bring over and accommodate 4000 Spanish refugee children.5 .6 He became the Warden of the Eventide boys’ home, and then at The Grange, a home in Street, Somerset, lent by the Clarks (apparently a Quaker family which ran the company still associated with shoes) In August 1940, he became co-founder, fund raiser and secretary of the “Refugee Children’s Evacuations Fund”, which increasingly supported Jewish refugee children and which appears to have been under the ‘umbrella’ of the Free German League.

Only briefly interned on the Isle of Man, he then became a board member of the Free German League of Culture and, along with Jurgen Kuzinski, organised the first international conference of anti-fascist scientists.7 He was also a member of the British-Soviet Society. He argued persistently for the need for a new post-Nazi German culture and education system. From 1945, he headed the remnants of the tiny exile KPD group, and was responsible for their members’ repatriation.8 (I guess that actually meant putting pressure on them to return to Germany to build the promised land.)

In September 1947 he returned to Berlin and became a SED activist and educational reformer.

1 Unfortunately, I have not been able to find out any further details about this Association or about Kamnitzers pre-1933 political activities. Much of the material for this article has been drawn from Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur: Biographische Datenbanke

2 Yet again, I have not found out more details. The National Archives web-site (where the records of Scotland Yard from that time are supposedly stored) has no record of Kamnitzer!

3 Hitler believed that the capture of oilfields in the Caucuses was an essential prerequisite to waging a prolonged war. Baku, situated on one of the world’s richest oilfields, alone produced 80 per cent of all Soviet oil. It consisted of several fields, including the new Nebit-Dagh ‘oil base’ near Krasnovodsk, which Hitler understood as indispensible to win the war. Stalingrad and the ‘need’ for a prolonged war made the issue of oil even more fundamental.( JOEL HAYWARD Hitler’s Quest for Oil: the Impact of Economic Considerations on Military Strategy, 1941-42)

4 Many letters between Hermann and Kate have been preserved which give a flavour of his vituperative disappointment about this pact, unusual amongst Party stalwarts.

5 The British Government’s position was deplorable. They refused to accept any Spanish refugees. Following the outrage at the bombing of Guernica in April, the government reluctantly agreed to allow in 4000 refugee children, if they had financial sponsors. Except for 250, they were redispatched to Spain in 1939, often with terrible results.