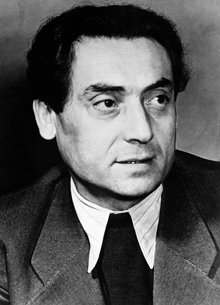

Max Zimmering was a youthful member of the Jewish ‘Blue and White’ youth movement and, in a typical transition, joined the KPD Youth Association in 1928. He wrote for the KPD paper: Die Rote Fahne and was its agit-prop leader in Dresden, where he lived. He also joined both the Jewish Workers and Employees Youth group and the Revolutionary Trade union Opposition (the KPD split-off)! In 1929, he joined the KPD.

While a poet, he trained as a decorator but was sacked for his union organising. He fled mid 1933 and first went to Paris, then Palestine where he worked for the illegal Palestine Communist Party. Then he went to Prague and worked for different left papers. After the Munich agreement, he fled to the UK in 1939.1

In 1940, the British government interned him as an ‘enemy alien’. Like many other KPD refugees, he was sent to Australia (which he referred to as ‘the involuntary trip around the world’) but was then returned to the Isle of Man camp, and, after much campaigning on his behalf, was finally released in November 1941.

Once back in London, he became editor of the Free German League of Culture’s (FGLC) magazine ‘Free German Culture’,2 and also worked for a number of anti-fascist magazines including “Rote Fahne”, based in Prague, ” Freie Deuthland ( established in Mexico in 1942, under the influence of the KPD exiles)3 and ‘Freie Tribune’ which, from 1943-1946, appears to have been a fortnightly anti-Nazi magazine geared towards German youth, based in London. He also participated in the KPD exile group.

In 1946, he was able to return to Dresden on a Czech Repatriation ‘passport’.4 There, he became an active, even militant, member of the SED.

1 The British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia was in effect set up as a sop by the British Government after the Munich Agreement. Many of those who came to the UK were not Czechs, but German and Austrian political refugees.

2 The FGLC was founded in 1939, providing the refugee anti-Nazis members with a social and cultural network. (C. Brinson and R Dove: Politics by Other Means: The Free German League of Culture in London 1939-1946 is just about the only study of it.) At its peak, it had some 1,500 members, but many more people attended. Its aim was to encourage anti-Nazi support and give some sense of solidarity. It produced a newsletter, Freie Deutsche Kultur; and did much besides. Advertising itself as non-partisan, it drew in a wide range of political support though KPD influence was strong.

But the Free German Movement, set up here as in other countries under Communist direction, was under the umbrella of the FGLC. Its leadership included important Communist figures like Johann Fladung, Wilhelm Koenen ( see separate biographies) as well as Max Zimmering and his brother Siegfried, who followed a similar political trajectory..

The FGLC soon split, partly as a result of a group of Jewish refugees whose interest was the right to remain in the UK, not to return to Germany.

3 Unfortunately, I have not found the link but my guess is he knew or was friends with Egon Kisch (see footnote below) who worked on this paper in Mexico.

4 He was helped by the fascinating figure; Egon Kisch. Kisch was arrested on the night of the Reichstag fire and charged with ‘high treason’ but released within months. He fled to France but then, In 1934, went to Australia to take part on the Anti-War Congress.(He was denied entry because of his communist sympathies. He literally jumped ship and finally gained entry after much popular protest.).

Back in Europe, he participated in 1935 in the 1st International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture in Paris, where he gave a report on ‘art as a form of struggle’. He then reported from the Spanish Civil war, interviewing members of the International Brigades.

Kisch managed to escape from France to the US in late 1939 and then went on to Mexico, where he wrote for the exile newspaper Free Germany. He returned to Prague in 1946, two years before his death.