by Merilyn Moos

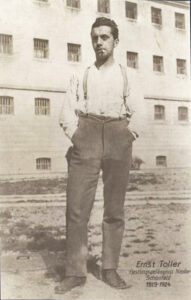

A figure who has received surprisingly little attention in the UK is Ernst Toller. (The honourable exception is Richard Dove’s ‘He was a German. A biography of Ernst Toller’, from which I draw.) Toller was a leading figure in the failed German revolution of 1918/19 and later became a strong campaigner in the UK against the Nazis. According to Richard Dove, once in exile, England was the country Toller felt most at home. But he was, like the other exiles, torn from the literary and political soil in which he had gained his political experiences and had flourished.

A figure who has received surprisingly little attention in the UK is Ernst Toller. (The honourable exception is Richard Dove’s ‘He was a German. A biography of Ernst Toller’, from which I draw.) Toller was a leading figure in the failed German revolution of 1918/19 and later became a strong campaigner in the UK against the Nazis. According to Richard Dove, once in exile, England was the country Toller felt most at home. But he was, like the other exiles, torn from the literary and political soil in which he had gained his political experiences and had flourished.

Toller, born in 1893, was disabused of any illusions about Germany when witnessing the horrors of World War 1 in the trenches. Initially influenced by Gustav Landauer’s brand of anarcho-syndicalism and pacifism, Toller was precipitated into the revolutionary movement by the outbreak of strikes in Munich, led by Kurt Eisner.1

On 29 October 1918, the sailors of the German fleet had mutinied when ordered to continue the fight against the British, precipitating mass strikes across much of Germany. On 7 November, Eisner marched on the cities’ barracks and persuaded the soldiers to join them; many soldiers, with their arms, deserted their barracks and flocked to support the demonstration. About 75,000 defense workers participated in the strike, demanding the end of the war. In Munich, there were over 10,000 strikers. Munich was paralysed by the strike. Eisner proclaimed the Peoples State of Bavaria in November 1918 and became its first republican leader. On 9 November, the Kaiser abdicated and the new republic was declared, the government to be run by the Social Democrat, Ebert.

The war ended but the upheavals rolled on. By the end of January, workers across Munich were on strike including at Krupps and other factories producing war material. Toller was elected onto a new strike committee formed to win support for the thousands on strike. A brilliant orator, he made many speeches to galvanise support at factory meetings.

Workers’ councils and committees were established but were never properly coordinated. Armed groups of workers and militia took over the streets of Munich. In a situation where neither the soviets nor the government held power, Eisner briefly formed a left coalition government with the Social Democrats in early January 1919. But Eisner’s People’s State of Bavaria was dependant on the Social Democrats to stay in power and he resigned. After Eisner’s assassination on 17 March 1919, the Social Democratic Hoffman succeeded as ‘Prime Minister’ of the People’s State of Bavaria.

But on 6/7 April 1919, the Sparticist leader, Max Levien, declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic in Munich.2 Again, workers’ militias were created, especially in the large metalworking companies and working-class areas. Hoffman under pressure from the workers movement fled.

But there were deep divisions over the viability of the Soviet, in particular between Eugene Levine3 representing the young German Communist Party (KPD) with Toller and other ‘independents’ (though the USPD was itself split). Levine understood how fragile this ‘revolution’ was, without proper grounding in workers councils and attacked the ‘pseudo soviet republic’.

On 7th April, the Bavarian Soviet republic was declared with Toller as its elected head. His ‘cabinet’ included anarchists and pacificists, such as the writer Gustav Landauer and playright Erich Muhsam. Toller issued an appeal for working class unity and for Hoffman’s government to be deposed. But lacking a sufficient working-class base and any sort of armed insurrection, the soviet stood little chance. On Saturday 12 April 1919, the KPD, led by Levinee, took over power..

In the meantime Johannes Hoffman had fled and began gathering about 8,000 troops, including members of the Freikorps, outside of Munich to attack the Bavarian Soviet Republic.4 There was a massive general strike in Munich, but nowhere else. Hoffman essentially blockaded Munich, which ran out of food.

It was Toller who became the ‘red general’ for an ‘army’ made up of armed workers and soldiers. Toller with his 30,000 republican guard clashed with Hoffman’s unit at Dachau on 18 April and repulsed them.

Ebert, the SD President of Germany, then gathered 30,000 Freikorps to take back Munich. Munich fell over a couple of days and the Soviet Republic ended on 1 May 1919 after holding power for six days. The revolutionary uprising was defeated in a bath of blood.

Toller was lucky. Condemned for high treason, he was merely imprisoned for 5 years; at least 700 other people were executed including Levine by firing squad.

Toller was deeply influenced by these events. He threw himself into writing poetry and plays which he wanted to always have a political purpose and which were almost all directed against the escalating threat of Nazism. Later in the 1920’s, he supported a defense block of workers’ organisations (as opposed to the KPD’s Third Period line). The Nazis’ growing anti-Semitism also alarmed him and led him to question his estrangement from Judaism and to ask-rhetorically- whether being Jewish meant he couldn’t be German, the country of his birth and the language he spoke.

By mid- 1932, the right-wing Government and the Nazis were threatening progressive writers. Toller first hesitated to flee when Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933 but whether by luck or design was speaking in Switzerland on the night of the Reichstag fire, when the SA stormed into his – and many other – anti-Nazis’ flats. That night the police and SA attempted to arrest, amongst others, Brecht, Erich Muhsam (of Bavarian fame), Heinrich Mann and Arnold Zweig, both writers, Georg Grosz, the caricaturist, John Heartfield, the artist, Erwin Piscator, the dramatist, and Kurt Hiller, of whom more anon, and many leading members of the KPD.

Toller was lucky to have Dora Fabian as a friend (see her biography). She got into his flat on the night of the fire and rescued two large suitcases of his papers. The rest of his literary archive basically ‘disappeared’. Toller was then deprived of German citizenship, much earlier than most on the left. In a speech on 1st April, 1933, Goebbels specifically denounced Toller as a public enemy of the Third Reich.

Toller stayed briefly in Switzerland but moved on to Britain by September 1933 where he lived in Hampstead till late 1936. He became active in International PEN. German PEN, which had already expelled him, was being torn apart because of its failure to criticise the book burning in Germany. Toller was invited to PEN’s International conference In May 1933 as a member of the English delegation. H.G. Wells, the chair, invited him to speak, whereupon he gave a rousing speech, emphasising the importance of uniting in opposition to the barbarism and irrationality of Nazism. The German and Dutch delegations walked out.

Toller was a witness at Münzenberg’s ‘Commission into the Burning of the Reichstag’.5 This was an unofficial investigation by a group of European lawyers established to investigate the cause of the Reichstag fire, held in England. It concluded, contentiously, that it was the Nazis themselves who started the fire.

Toller had already visited the UK in 1927, 1928 and 1929. He had met with the ILP and become involved in the setting up of the League against Colonial Oppression with Münzenberg, a German KPD member, acting for the Comintern (with a commitment to the Third Period line). Fenner Brockway, a leading ILP member, was the League’s first International Chair, later replaced by James Maxton.

Toller knew Brockway and was close to the ILP, giving advice and contacts for illegal work in Germany.6 They had close relations with some of those opposing Hitler. Brockway, representing the ILP, had no problem endorsing the supposed ‘illegality’ of those resisting the Nazi regime post 1933.7 The ILP had ties with members of the USPD, some of whom Toller was still in contact with. (The SPD were understood as supine.) Brockway was involved in organising forged passports for refugees from Nazism, and getting refugees out of Germany and the Saarland, without valid passports, right up to the outbreak of war. They also printed and smuggled into Germany 3 inches square newspapers in support of struggle against Nazism.8

Toller too campaigned for the rights of refugees, which he viewed as part of the struggle of humanity over barbarism. Toller became convinced that there would be a European war and, in a shift from his earlier position, argued for the importance of the popular front against fascism and became, at least temporarily, sympathetic to the Soviet Union as a result.

Toller had become increasingly convinced he needed to emphasise political, rather than literary, activity. He wrote for the left-wing Reynolds News (hands up those of us who still remember this paper!), explaining that one has to always struggle for political freedom against the power of the State, the capitalist system and the ruling class.

The publication of virtually his entire work in Britain gave him relative financial independence, which he used to launch a major campaign to help fellow-refugees in Britain and France. Toller was in great demand as a speaker and became a popular campaigner in the UK against Nazism. He spoke at a variety of writers’ conferences, speeches which all received wide publicity, as well as at the National Council for Civil Liberties, the Workers Education Association, various universities and the Anglo-Soviet Friendship League. Toller’s denunciations focused on Nazism’s attack on intellectual freedom and on innocent German writers, maybe to avoid being seen as politically active in order to avoid deportation.

In 1938, Toller who by then had moved to the US, travelled to Spain, where he spoke to International Brigades on the Ebro front. He organised relief for Spanish civilians. He argued that Germany’s involvement was a dress rehearsal for a wider conflict and was critical of appeasement and the sham of “non-intervention”. On 21st September 1938, he returned to London and campaigned for support for the Spanish Relief Plan. At this point, even Blum in France held a non-interventionist perspective. The British government did not want to upset the German government. On August 26, 1938, in Madrid, Toller gave a radio speech urging all the democratic powers, but especially President Roosevelt, to lend their support. Note how Toller had moved from a ‘united’ to a ‘popular front’ position. Toller travelled to France, Great Britain, the Scandinavian countries and finally the US in support of his relief project. But the republic lost.

In the spring of 1939, Toller, back in the US, exhausted, deeply disheartened by the defeat of the Republicans, the successes of the totalitarian regimes and cut off from both Germany and Britain, sank into depression and killed himself on the 22nd May 1939. In his eulogy at Toller’s funeral, the writer, Sinclair Lewis, described Toller as “a symbol of the revolution.”

1 Ever since, there has been a debate, sometimes heated, about how far Toller’s initial anarchistic tendencies continued to influence his politics.

Eisner (1867 – 1919), a journalist and theatre critic, was a member of the USPD from 1917, a breakaway from the SPD on an anti-war platform, who had been deeply opposed to the First World War from its beginning and the Social Democrats collusion with it. Arrested in 1919, Eisner was convicted of treason for his role in inciting a strike of munitions workers in 1918 but, upon release, was assassinated by far-right German nationalist Count Arco-Valley in Munich on 21 February 1919.

2 Neither the soviets nor the government held power. Eisner briefly formed a left coalition government with the Social Democrats in early January 1919. However, Eisner was outmanoeuvred, and in February 1919 decided to resign but was murdered on his way to Parliament .

3 Leviné was dispatched by the KPD Central Committee to avoid another blood bath as in Berlin and to emphasize the importance of workers’ councils.

4 The Freikorps was effectively the old German Army, banned by the victorious Western allies, but now operating as mercenaries under the command of rightist generals. They were the force which both destroyed the Bavarian revolution and the uprising in Berlin and were to have a strong influence on the SA.

5 On February 27, 1933, the Reichstag was set on fire. The Dutch left-winger Marinus van der Lubbe was arrested soon after. The Nazi leaders accused the KPD of having committed the arson. The Nazis had been in power less than a month; the Reichstag fire provided the perfect excuse for the arrest of thousands of Communist (and to a lesser degree Social Democratics) and others active in the workers movement were arrested ( many later murdered).

6 Toller’s almost unknown play; ‘Berlin’, produced in 1930, using ‘documentary realism’, depicts a scene based on Brockway’s denunciation of British policy in India in the House of Commons in July 1930 (for which Brockway was suspended!)

7 Brochway, initially a pacifist after the First World War, as General Secretary of the ILP, went to Spain to rescue those opposing and being murdered by the Communists, rather than from the Francoists. His particular concern was George Orwell. The ascendency of fascism persuaded him that one has to fight against fascism.

8 https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80004783

It has unfortunately not proved possible-at least so far- to find out the exact nature of Toller’s involvement in these activities